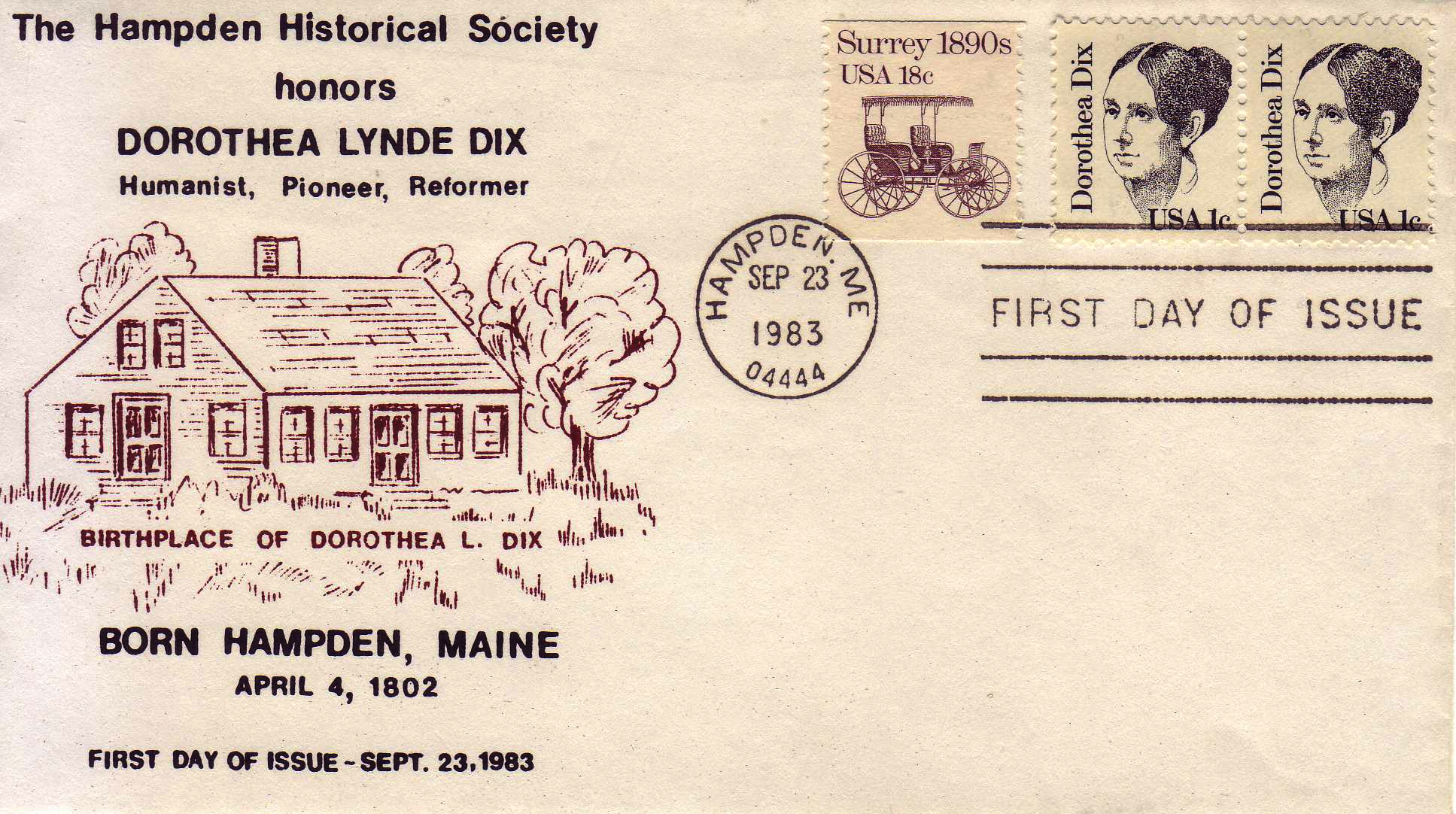

Dorothy Day was born in Brooklyn Heights New York on November 8, 1897. Her father  John Day was a sportswriter. Dorothy’s mother was a kind woman whose example of warm-hearted sharing with anyone in need would affect Dorothy for the rest of her life.

John Day was a sportswriter. Dorothy’s mother was a kind woman whose example of warm-hearted sharing with anyone in need would affect Dorothy for the rest of her life.

Dorothy’s family had moved to San Francisco in 1904 and were there when the great fire destroyed most of the city in 1906. Her mother joined her neighbors in gathering food and clothing for the displaced families who were sleeping in the park in Oakland. Within a few weeks the Day’s would move to Chicago because the newspaper office where John worked was burned down by the fire.

John Day could not find work and began to write a novel. Mrs. Day struggled to put meager food on the table. It was during this time that Dorothy met several kind Catholic women who reflected the love of Christ to her. She never forgot them. Eventually John Day was hired by a newspaper and the family moved to a nicer home on the north side of Chicago. Dorothy was an excellent student in her high school. She loved languages and studied Latin and Greek.

Dorothy’s older brother Donald took a job with a small paper. This paper sympathized with the rising labor movement. Through Donald’s influence Dorothy studied the works of Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, and Jack London, writers who were calling attention to the injustices of the class system in the industrial world. At this time Eugene Debs became a hero in Dorothy’s eyes.

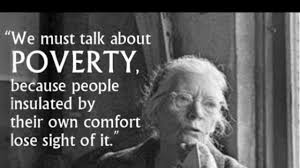

Though her parents did not claim to be religious – Dorothy’s father even claimed to be an atheist – Dorothy loved to read the Bible. She was confused about God in her early years but gradually came to see how Christ manifested love to people, especially the marginalized. She saw that Christ had rejected the “things of this world” but she did not believe that God meant for people to live in abject poverty either. Dorothy recalled how her mother and the people in Oakland responded to the poor in the aftermath of the San Francisco fire. She dreamed of the day when all people, not just the social workers and missionaries, would be open-handed and generous to the poor.

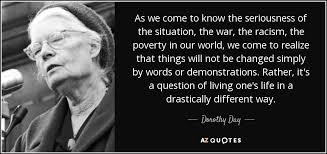

The greatest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us?*

Dorothy’s father lost his job again. She did not know if she could afford to go to college but because of her excellence in Latin and Greek she won a scholarship to the University of Illinois. She began to attend in 1914. She enjoyed her independence very much but never forgot the poor and downtrodden. After two years Dorothy’s father got a job in New York City. Dorothy decided to leave school and go to New York to be close to her family.

Dorothy looked for a job at a newspaper and finally found one in 1916. She worked for several socialist newspapers and also took part in the anti-war activities of many of her friends opposing the military draft. People in our day have come to accept US involvement in war but in 1917 many Americans wanted to let Europe solve its own problems. Dorothy may have been accused of being anti-patriotic when Wilson made laws against speaking out against his policy of war. Later during the Vietnam war many would agree with Dorothy’s belief that America should not interfere in wars. In spite of the changing attitudes of Americans about fighting in wars, Dorothy would remain a pacifist.

It should come as no surprise then that Dorothy would take part in the women’s suffrage movement. On one occasion after a protest Dorothy and other suffragettes were arrested and put in prison. They were treated abominably. It was hard for her to believe that human beings could treat fellow humans that way. “I had an ugly sense of the futility of human effort, man’s helpless misery, the triumph of might. Man’s dignity was but a word and a lie. Evil triumphed,” she later wrote. Dorothy struggled with her faith in the face of such injustice.

In the next few years Dorothy experienced love, marriage, and the birth of a child. With her common law husband, Forster Batterham she had a daughter, Tamar in 1926. During this time Dorothy was renewing her growth in her Catholic faith and she wanted to be baptized and to get Tamar baptized. The whole discussion of religion bothered Forster and eventually he left his wife and daughter. He would only return at the very end of his life to visit Dorothy when he was dying of cancer. At that time they would make amends and renew friendship. Dorothy always remained devoted to Tamar for the rest of her life, always finding time to be with Tamar and her children even during Dorothy’s busiest years.

The 1930’s was the time of the Great Depression. Dorothy began to seek ways to live out her Catholic faith in service to the poor. In 1932 her prayer was answered when Peter Maurin knocked on her door. He was a French immigrant who had a vision for a society that really lived out Christian virtues.

Together Peter Maurin and Dorothy founded a newspaper called the Catholic Worker. The goal was to start houses for the poor and farming communes. Over the next few years the idea would blossom until it was replicated worldwide.

Dorothy was asked to speak many times. She was really shy but she knew that her talks were spreading the philosophy of the Catholic Worker. Dorothy longed to see a time when everyone would serve humanity through each one’s individual efforts. Putting aside her fear of speaking in front of crowds, Dorothy began to speak to school groups, women’s clubs, conventions, and other social workers. Dorothy bravely explained the concept of service to those in need as real Christianity.

I really only love God as much as I love the person I love the least.

Dorothy practiced what she preached. Choosing voluntary poverty, she lived in a small upstairs room in one of the houses of hospitality. Lest one think that she thought of herself as a martyr she maintained that she was privileged. All she needed was a bed and bath and two large shelves full of books. After all, if you’re so busy serving others what else do you need in life? Dorothy was happy.

During World War II Dorothy worked extra hard in the hospitality houses due to the shortage of men. Her pacifist stance was unpopular but in years to come many would see that it was consistent for this woman who wanted all people to love one another.

Dorothy welcomed the strides that the African-Americans made during the 1950’s. On one occasion Dorothy visited an integrated commune. There were strict segregation laws in Georgia and the people in the commune received many threats. Dorothy was warned that there could be violence. One night, fifty-nine year-old Dorothy was on watch duty when suddenly she heard screeching tires. Soon a shower of bullets was rained down on the car in which she was sitting. Dorothy had been criticized for her beliefs, and spent time in prison; now she nearly lost her life in the cause of justice.

In the 1960’s Dorothy would go to the Vatican in Rome to urge the Church to make a strong anti-war statement. Dorothy was thrilled when many protested the Vietnam war.

While in Rome she joined a ten-day fast to bring the attention of the public to the starving millions of the world.

In the 1970’s Dorothy marched with Cesar Chavez to protest the mistreatment of farm workers. One thousand protesters were arrested, Dorothy among them. By this time Dorothy was in her seventies and beginning to look a little frail. However, she took her two week incarceration stoically, remarking, “If it weren’t a prison it would be a nice place to rest.”

Dorothy was beginning to tire. She turned down speaking engagements but continued to write for the Catholic Worker and to visit with family and friends.

Dorothy was distressed about the changes in the world in the 70’s. Even the Catholic Church seemed to be changing. But she found consolation in her Bible. As she had done since the earliest days of her conversion she read from the Psalms every morning. Reading her Bible, Dorothy was comforted in her belief that Jesus Christ is our example of love and living.

My strength returns to me with my cup of coffee and the reading of the psalms.

In her old age Dorothy received many honorary degrees and awards. During her life she had written many books including; “From Union Square to Rome”, “House of Hospitality”, “Loaves and Fishes”, “The Long Loneliness”, and “On Pilgrimage”.

In 1979 the hospitality house where Dorothy was living was sold and she moved back to New York City into a hospitality house called Maryhouse. In her quarters in this house Dorothy passed her time reading, writing, and receiving visitors. On November 29, 1980 Dorothy died peacefully in her room. Her beloved daughter Tamar was with her during her final hours. Her final resting place is the Cemetery of the Resurrection on Staten Island.

*Throughout this essay I sprinkled appropriate quotes from Dorothy’s writings.