Faithful Women

Throughout the centuries many women have found themselves in leadership positions while they were trying to remain faithful to God’s calling. These women were in circumstances where they could not remain silent about the injustices in the world around them. They spoke out because they were honoring God by working to care for the poor and suffering. They tried to alleviate suffering because they loved the Lord Jesus and wanted salvation and healing for others. They were not seeking leadership positions. Through their faithfulness, God thrust them into positions where they could lead others.

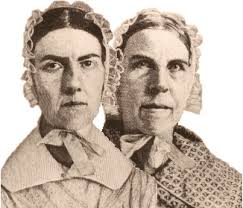

The four women in these reviews lived during a span three centuries: Margaret Fell Fox (seventeenth century), Sarah Osborn (eighteenth century), and the Grimke sisters (nineteenth century). During these centuries women were not supposed to be speaking in front of groups containing men. Yet, these women boldly led Bible studies or held meetings to share God’s love and truth because they were called of God to do so. The stories of their lives are an inspiration to women today who seek to serve God with their individual callings.

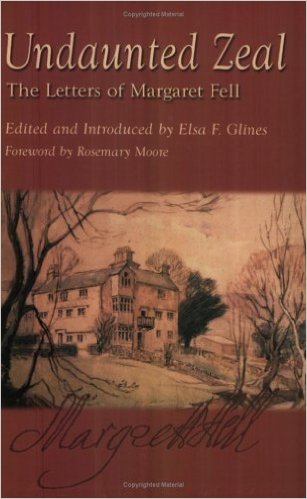

— Glines, Elsa F., Editor, Undaunted Zeal: The Letters of Margaret Fell, (Friends United Press, Richmond, Indiana 2003).

— Glines, Elsa F., Editor, Undaunted Zeal: The Letters of Margaret Fell, (Friends United Press, Richmond, Indiana 2003).

Margaret Askew Fell Fox (1614-1702) was a woman of undaunted courage. She lived through one of the most tumultuous times in English history. This is the same time period in which John Bunyan and many other non-conformist Christians were imprisoned for their faith. Through all of the upheavals in government and religious policies Margaret kept a steady faith in God and His Word. She always put God first even if it meant going to prison. She strived for liberty of conscience.

Margaret wrote many letters while in prison under her own name – Margaret Fell. (She did not marry George Fox until 1669, one year after she got out of prison.) In this book, Elsa F. Glines publishes 164 letters of Margaret Fell. The book is divided into three parts for three periods of Margaret’s life. Each section begins with a short biography of that period of Margaret’s life. The introductions to the letters contain a wealth of historical background that is interesting to history students.

Whether you are interested in the history of the Friends, or Quakers, or just in the topic of religious freedom, you will enjoy this book.

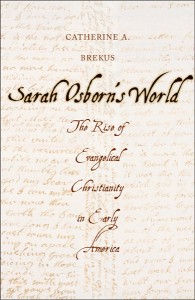

— Brekus, Catherine A., Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of  Evangelical Christianity in Early America, (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2013).

Evangelical Christianity in Early America, (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2013).

While most people have heard of Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and Gilbert Tennent, few know who Sarah Haggar Wheaten Osborn was. Yet during this time of the Great Awakening a religious revival occurred at Sarah Osborn’s house. Decades before Americans were taking abolition seriously, Sarah brought both free and enslaved black men and women into her home and taught them the Bible. Sarah’s life made a difference to thousands.

Through all of the many afflictions in her life, Sarah Osborn (1714-1796) maintained her faith in God. She struggled through wars, poor health, the deaths of loved ones, and conflicts at her church. Today she has been all but forgotten, but Sarah Osborn deserves to be remembered for the part she played in the many lives of others in the eighteenth century. Hundreds of less fortunate people praised Sarah for her faith, courage, and humble service. Sarah believed that God used her suffering to draw her closer to Him and to be an example to others.

In this book, Catherine Brekus relates Sarah’s life through the backdrop of eighteenth century religion. She gives a good history of the rise of evangelicalism that will be interesting to those who love biography, history, and theology. Sarah’s life is still an encouragement to believers today.

— Lerner, Gerda., The Grimke Sisters from South Caroline: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition, (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2004).

— Lerner, Gerda., The Grimke Sisters from South Caroline: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition, (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2004).

The Grimke sisters, Angeline and Sarah, have been pretty much forgotten in our day but in the nineteenth century they were well known in abolitionist circles. They made history in speeches against slavery as well as in publishing tracts calling for an end to that evil institution. They recognized that slavery and discrimination, though connected, were two separate issues and fought against both. In 1838 Angelina made history as the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States.

In this book, Gerda Lerner tells the amazing story of these two southern born women who became famous for their fight for equality for blacks and for women. The book reads like a novel and is hard to put down. Gerda Lerner also includes some of the famous speeches of Angelina (the better speaker of the sisters) and excerpts from the writings of Sarah Grimke. (See below.)

Many women today can thank Angelina and Sarah for their courage in pioneering justice and equal rights for both blacks and women.

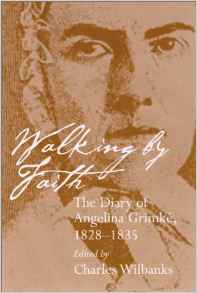

— Wilbanks, Charles, Editor., Walking by Faith: The Diary of  Angelina Grimke, 1828-1835, (University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2003).

Angelina Grimke, 1828-1835, (University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2003).

Even as a young girl Angelina Grimke had deep faith in God. Angelina’s prayer was:

O that I might live religion – how striking the exhortation of the Apostle – present your bodies a living sacrifice, Lord enable me so to live that every day I may sacrifice my own will to thine. (From her diary, December 25, 1828)

Angelina Grimke Weld was born in 1805 in South Carolina. She was the youngest of fourteen children born to slaveholders John Grimke and Mary Smith Grimke. Her older sister Sarah was thirteen when Angelina was born. Sarah doted on her baby sister Angelina and the two remained close until the end of their lives.

In this book, Charles Wilbanks intersperses biographical sketches of Angelina’s life with the diary excerpts over a period of about 8 years. It is a fascinating story of how one woman went from a slaveholding family to being a leader in the abolitionist movement. The reader witnesses Angelina’s spiritual growth and social maturity from her earliest recorded thoughts (age 22) to the writing of a letter to the editor for William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper (age 30). This letter to the editor propelled her into the public eye as a leader in the fight for abolition. Her diary ends when her public career begins. At this point, I suggest you read Gerda Lerner’s book if you already haven’t done so!

— Grimke, Sarah Moore, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and  the Condition of Woman: Addressed to Mary S. Parker…, (Originally published by Isaac Knapp, 25, Cornhill, 1838).

the Condition of Woman: Addressed to Mary S. Parker…, (Originally published by Isaac Knapp, 25, Cornhill, 1838).

Though of the two Grimke sisters, Angelina was the principle speaker, Sarah was just as passionate about justice for the downtrodden. She left writings that have come to the attention of historians today because Sarah was so far ahead of her time in her thought. Here is an excerpt from Letter #1:

“On the Original Equality of Women”

“Had Adam tenderly reproved his wife, and endeavored to lead her to repentance instead of sharing in her guilt, I should be much more ready to accord to man that superiority which he claims; but as the facts stand disclosed by the sacred historian, it appears to me that to say the least, there was as much weakness exhibited by Adam as by Eve. They both fell from innocence, and consequently from happiness, but not from equality…. The consequence of the fall was an immediate struggle for dominion, and Jehovah foretold which would gain the ascendancy; but as he created them in his image, as that image manifestly was not lost by the fall, because it is urged in Genesis 9:6, as an argument why the life of man should not be taken by his fellow man, there is no reason to suppose that sin produced any distinction between them as moral, intellectual and responsible beings.”

The entire book is especially fascinating when you remember is was written in the 1830’s, well before the women’s suffrage movement. Today woman have freedoms that we take for granted – education, jobs, the vote, and a public voice. Sarah could only dream about and write about those things. She was very courageous to speak out for the truth in 1838. We can be very thankful for women like Sarah Grimke who were pioneers in the suffrage movement.