Significant Nineteenth Century Christian Women

For the last few months I have posted stories on significant women from the nineteenth century. Many thousands of people were helped by their work. Untold thousands today are still benefitting from the organizations or movements founded by these women.

Relive the fascinating lives of Dorothea Dix, Mary Lyon, and Clara Swain through these biographies and their personal writings.

— Lightner, David L., Asylum, Prison, and Poorhouse: The Writings and Reform Work of Dorothea Dix in Illinois, (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1999).

Though little recognized today for her tremendous work of reform, Dorothea Dix was one of the most famous women of her time. In this first of two books that I recommend you will find accounts, written by Dorothea herself, of what the living conditions were like for the insane, prisoners, and the poor. Many documents that are reprinted by the author recount her efforts to get the laws changed in order to provide more compassionate treatment for the insane.

Though little recognized today for her tremendous work of reform, Dorothea Dix was one of the most famous women of her time. In this first of two books that I recommend you will find accounts, written by Dorothea herself, of what the living conditions were like for the insane, prisoners, and the poor. Many documents that are reprinted by the author recount her efforts to get the laws changed in order to provide more compassionate treatment for the insane.

This book focuses on these documents and their significance. One example of a document is a “Memorial” that she presented to the legislature of Massachusetts asking that the budget be increased to include money to improve the State Mental Hospital at Worcester. Many improvements were made in the state hospitals and prisons thanks to Dorothea. She continued traveling to many states seeking similar changes.

While the author concentrates on his home state of Illinois, he gives a fine account of Dorothea’s life and accomplishments. The last chapters recount the Dorothea’s tremendous legacy – hundreds of thousands of people down through the years have benefitted from the reforms that she initiated.

— Colman, Penny, Breaking the Chains: The Crusade of Dorothea Lynde Dix, (ASJA Press, New York, 2007).

Those looking for a biography that is more “story-like” will enjoy this book. Penny Colman is a fine author of many books. She relates Dorothea’s childhood and early life and how they contributed to the campaign that Dorothea went on at nearly forty years of age. You will be impressed as you learn more about the personal fortitude and courage of Dorothea Dix. It never ceases to amaze me how just one person can make such a difference! Dorothea Dix is especially extraordinary because she was only a “retired school teacher in frail health without wealth or power to support her cause” (Page 55).

Dorothea Dix contributed her efforts to reforming the treatment of the mentally ill who were often housed in prisons in horrible conditions. Dorothea did this by changing the way people thought about mental illness. “It is time that people should have learnt that to be insane is not to be disgraced; that sickness is not to be ranked with crime; and that mental disability is almost invariably the result of mere bodily ailment” (Page 73). Today we take it for granted that mental illness is not a crime. It’s hard to imagine how people thought that it was in the nineteenth century. Dorothea called for Christians to care for the poor as the Savior did. Her campaign resulted in the building of 32 institutions in the United States where the mentally ill could be cared for in a more compassionate way.

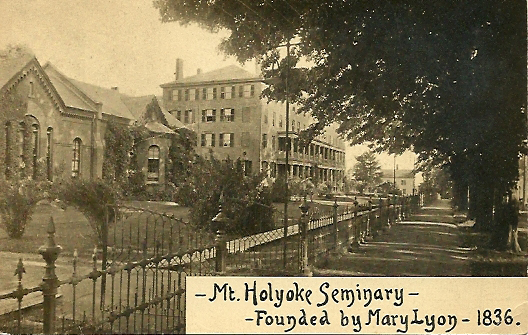

— Green, Elizabeth Alden, Mary Lyon and Mount Holyoke: Opening the Gates, (University Press of New England, Hanover, New Hampshire, 1979).

This book is about another obscure, young, penniless teacher from the early nineteenth  century whose life made a difference to thousands. Mary Lyon believed that women should be able to get a college education. In 1837 this was an unpopular idea. In the early eighteen hundred’s it was thought that only men should get an education; it was thought to be wasted on women. Some said that it was impractical, unwise and even unchristian.

century whose life made a difference to thousands. Mary Lyon believed that women should be able to get a college education. In 1837 this was an unpopular idea. In the early eighteen hundred’s it was thought that only men should get an education; it was thought to be wasted on women. Some said that it was impractical, unwise and even unchristian.

Mary Lyon believed that women should honor God with their gifts of intelligence. Mary struggled for three years raising the money for her institution of higher education for women. She set out mostly on foot going door-to-door to raise the $30,000 needed to open her school. She appealed for donations in the name of religion and based on the principle that education of the daughters of the Church called as rightfully for the free gifts of the Church as does that of her sons.

Man people agreed with her and in spite of so many others who discouraged or disdained her efforts Mary raised the money. Male town officials in Hadley, Massachusetts donated $8,000 and so the site for Mount Holyoke Female Seminary was located there.

Elizabeth Green tells the exciting account of Mary’s life and her accomplishments. Her girl’s school set the standard of quality education for years to come.

— Hartley, James E., Mary Lyon: Documents & Writings, (Doorlight Publications, South Hadley, MA, 2008)

After reading Elizabeth Green’s biography of Mary Lyon I couldn’t wait to read a book containing her letters and other writings. James Hartley put this compendium together in such a way as to allow readers to get a glimpse of Mary’s life and trials through her writing.

Hartley gives credit not only to Elizabeth Green but also to Edward Hitchcock. Edward Hitchcock was one man who supported Mary Lyon. He was the president of Amherst College in the early 1800’s and a friend and mentor of Mary. After her death he collected her letters to use in a biography. Praise God that he did because over time many of her letters were lost and we would not have such a remarkable account of one of the most important women of the early nineteenth century without his collection.

Mary was very modest and would not let anyone even think of naming the seminary after her. Mary’s missionary fervor was genuine. She believed that the income from Mount Holyoke belonged to the Lord. She only accepted a modest salary. She gave much of that meagre income to the poor and left her personal property to the American Board of Foreign Missions when she died. The school itself contributed nearly seven thousand dollars to foreign missions in the last seven years that Mary was there.

Her fervor was caught by her students. Over the twelve years Mary directed the school, hundreds of women became missionaries, teachers or wives of missionaries. Twelve students went on to take the Gospel to the Indians in the western United States. Scores of pastor’s wives were trained at Mount Holyoke.

Women owe Mary Lyon a big thank you for stepping out and founding a female seminary.

— Swain, Clara A., A Glimpse of India, (James Pott & Company, New York, 1909). (My copy is a reprint from: Classic Reprint Series, “Forgotten Books”, London, 2015).

Clara A. Swain was also a first among women in the nineteenth century. Clara Swain has the honor of being the first fully accredited missionary sent out by a Christian organization and the first woman physician in India. Clara also had the privilege of “standing before kings” when as a woman she was allowed to be the palace physician for an Indian Rajah’s family.

Clara A. Swain was also a first among women in the nineteenth century. Clara Swain has the honor of being the first fully accredited missionary sent out by a Christian organization and the first woman physician in India. Clara also had the privilege of “standing before kings” when as a woman she was allowed to be the palace physician for an Indian Rajah’s family.

Upon arriving in Bareilly, India, Clara wasted no time but started a dispensary immediately. As the only women doctor within a 200-mile radius she was soon busy making over 250 house calls in her first year and treating 1000 patients.

This book is a collection of her letters that give us a wonderful idea of what it was like to be a doctor in India in 1870. Clara’s letters to her family and friends back home were detailed and colorfully written. In them we follow her progress as she opened hospitals, nursing schools, and dispensaries. She also led Bible studies and taught the women to sing Christian hymns.

Clara was as tireless in her devotion to her work as Dorothea Dix and Mary Lyon. Like Dorothea and May, Clara has many thousands of spiritual children on earth and in Heaven.