March is Women’s History Month. Last week we honored a brilliant woman from the eighteenth century, Maria Gaetana Agnesi who was the first person to publish a calculus textbook for students. Maria Gaetana became an example for women in the field of mathematics. This week we will honor two more outstanding women who helped to pave the way for recognition of women in the medical field – Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell.

If any college or medical school dared to refuse a female student her hard earned degree today just because of her gender, that school would be in big trouble. Not only could there be a lawsuit pending, but society would be outraged. We cannot imagine a woman not getting a degree or a good job or a position in an organization just because she is a woman. As women today we take it for granted that we should be treated with respect. We expect to be paid fairly and given our due for our hard work.

This has not always been the case. In the mid-nineteenth century women were seldom allowed to attend college and less seldom given the degrees that they earned. Society was wary of giving women the idea that they could do anything outside of the home. While we agree that marriage and family are high callings, society should not limit women from where God has called them.

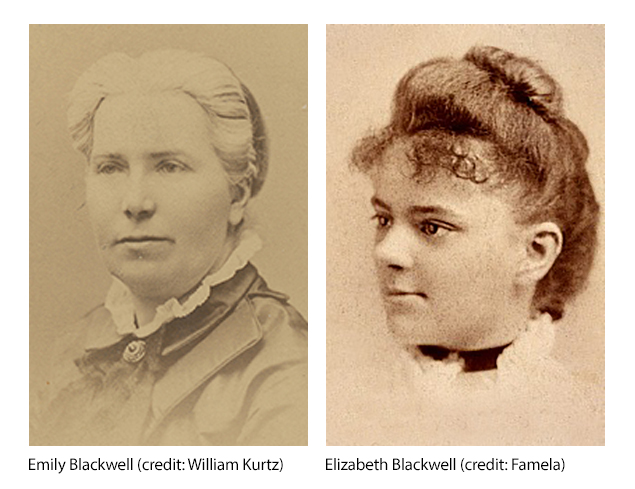

Today, the reason women can go to medical school and go on to become doctors is thanks to pioneering women like Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell.

As a girl Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) was not interested in being a doctor. Years later in her book, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, published in 1895, Elizabeth said that she “hated everything connected with the body, and could not bear the sight of a medical book… The very thought of dwelling on the physical structure of the body and its various ailments filled me with disgust.”

Then one day a close friend who was dying explained to Elizabeth that she would have been spared her worst suffering if she had had a woman doctor. Things changed for Elizabeth. She now knew that she wanted to help women as a physician.

Emily Blackwell (1826-1910) on the other hand wanted to follow in her older sister’s footsteps and enter the medical field. Emily struggled as Elizabeth did to get medical training. After finally getting degrees in medicine the sisters sought experience in clinical medicine. When Elizabeth and Emily were rejected by many medical facilities that distrusted women doctors they built a hospital of their own to treat women with their unique female health problems.

The Blackwell family was an amazing group of people. Samuel and Hannah Blackwell emigrated from England in 1832 with their nine children eventually settling in Cincinnati, Ohio. Samuel Blackwell Sr. started a farm to convert beets into sugar because he wanted to reduce the dependence on slave-produced cane sugar. The Blackwell’s were ardent abolitionists.

Samuel and Hannah Blackwell were deeply religious and raised their children with a sense of social justice that was unusual for their time. This included the view that women should be educated to live in a growing and changing world. During an era when girls were expected to study only the subjects that prepared them to be good wives and mothers, the Blackwell’s saw to it that their daughters as well as their sons studied mathematics, science, literature, and foreign languages. Samuel and Hannah also encouraged their children to engage with the world of nature asking questions and expressing their thoughts freely.

Elizabeth was born into this unusual family in Bristol, England in 1821. She was 11 years old when their family moved to America in 1832. Sadly, their father died in 1838 leaving the care of their family to her older brothers.

The girls in the Blackwell family were all intellectuals – both Elizabeth and her sister Emily became doctors. Their brothers were no doubt inspired by their amazing sisters to marry intellectual women as well. Henry Blackwell married Lucy Stone, a brilliant woman and advocate for reform. Samuel Blackwell Jr. married Antoinette Brown, first woman to be ordained as a minister in a Congregational church.

Though the Blackwell’s were advocates of education for women they still held somewhat to the traditional expectations for women in their day. The most acceptable career for women outside of the home was teaching. Elizabeth therefore began her early career in teaching. It was when a dying friend told Elizabeth that a woman physician would have spared her much agony that Elizabeth decided to become a doctor.

As a woman Elizabeth knew that it would be difficult to become a physician. Most of her family and friends were discouraging, but eventually two physician friends let her read medicine with them for a year. Elizabeth applied to many medical schools before she was finally accepted at Geneva Medical College in New York in 1847.

In 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to receive a medical degree from an American medical school. She then traveled to Europe to study for two more years under English and French doctors. While undergoing training in midwifery she contracted an eye disease from a patient. Elizabeth lost her sight in one eye and gave up on the idea of becoming a surgeon.

Returning to New York Elizabeth tried to gain a practice in a dispensary. She was refused. So she opened her own dispensary in a rented room treating up to three patients a day. In 1854 Elizabeth was able to buy a house and continue to enlarge her practice. In 1856 her sister Emily and another woman physician, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska joined her. In 1857 they founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Here they provided medical care for the poor and offered opportunities for other women to receive training in the medical field.

Emily Blackwell was a sensitive and brilliant woman. Like her sister she tried teaching as a young woman. She hated it and talked to her sister Elizabeth about practicing medicine together. Emily began to look for medical training and received rejections by 12 medical schools before finally being accepted by Rush College in Chicago. They only let her study for one year. She was then accepted by Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, where she graduated with highest honors in 1854. Like her sister, Emily went to Europe to study medicine.

Returning to New York, Emily and a young German-born woman of Polish ancestry, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, joined Elizabeth in opening the hospital for women. Since Elizabeth’s eyesight was poor, Emily did the surgeries.

The women also pioneered in the medical industry by offering the first in-home care to poor patients. They not only saw to the medical needs of the women and children but also offered them training in better health care practices and sanitation.

Elizabeth and Emily continued to campaign for medical training for women. When it became clear that no one was willing to help they started their own training program in 1868. They offered a full three years of study at their infirmary that included clinical experience.

In 1869 Elizabeth moved back to England to continue her medical work. Emily became the full-time administrator of the hospital. Under her direction the hospital and medical school did so well that she needed to move it to larger quarters. In the 1870’s the training program was expanded from three years to four and a comprehensive training course for nurses was added.

Finally in 1899 Cornell University Medical College began accepting female students on an equal basis with men. Emily could rejoice that all of their hard work paid off. Now that women could study medicine freely she transferred her students to Cornell and retired. Her very capable staff continued to run the infirmary, still in existence today as NYU Downtown Hospital.

Emily Blackwell spent her retirement years between her homes in New Jersey and Maine. Elizabeth continued to live in England. The sisters saw each other one last time in 1906 when Elizabeth came to visit Emily in the United States.

A year later Elizabeth suffered from a severe fall while traveling in Scotland. She never fully recovered from it. In May 1910 Elizabeth suffered a stroke and died in England. A few months later at her home in Maine, September 2010, Emily died from an inflammation of the intestines.

Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell paved the way for women to become physicians. 360 women graduated from the school that they established. Today due to their courageous pioneering efforts many thousands of women are working in the field of medicine. We can all be thankful that they were willing to give their lives to the cause of helping others.