In the course of Agnes’s life she had on many occasions blessed a Greater Providence, but never more ardently than when she stumbled across this blackened wodge of text. How fortunate that her brother-in-law had prevented her from visiting St. Catherine’s six years earlier. How glorious now that former disappointment! Had she and Grace not been stopped at Suez by Gibson’s telegrams, they might have made the desert crossing and passed some time pleasantly enough with the monks, but as tourists – nothing more! She would not have read Rendel Harris’s description of the ‘dark closet’ or have studied Syriac. Nor would she have had any connection to the University of Cambridge, or the interest of its scholars in directing her enquiries; and of course no signed and stamped letter of introduction from the vice-chancellor to ease her progress in Cairo. She would not have had the faintest idea about cameras or the general familiarity with antiquities and manuscripts gained simply from having been married to Samuel Lewis, the keep of the Parker Library. *

(Continued from Part 1, February 23, 2016)

Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson set out on the difficult and dangerous journey to St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai in 1892. They had longed for nearly ten years to be able to return to St. Catherine’s Monastery and view the Syriac manuscripts that were supposed to be hidden away in a dark closet. Circumstances, including their brief but happy marriages precluded them from fulfilling their dream.

Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson set out on the difficult and dangerous journey to St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai in 1892. They had longed for nearly ten years to be able to return to St. Catherine’s Monastery and view the Syriac manuscripts that were supposed to be hidden away in a dark closet. Circumstances, including their brief but happy marriages precluded them from fulfilling their dream.

Agnes and Margaret would later reflect that had they set out any earlier on this adventure they might not have been successful. They believed in a providential God and realized that going on the trip had to wait until His perfect timing.

During their wait, God was preparing them in ways they didn’t understand before they could set out. Agnes was disappointed when her brother-in-law, James Gibson sent her warnings not to go to Sinai because he thought it was too dangerous. She honored him and returned home. Later, she and her husband, Samuel Lewis, would travel to other places. She never lost her desire to see the Holy Land.

It is very exciting to see how the sisters would accomplish the desire of their hearts. They were in mourning as widows but did not sit around for long. Agnes and Margaret would later understand the reasons why they were chosen to find the Sinai Palimpsest even though many men had failed and even though they had to wait. God granted them the success where others had failed.

In the first place, the monks at St. Catherine’s Monastery did not trust European scholars any more. In 1859 the famous Constantin von Tischendorf visited the monastery in search of the Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest known copies of the Bible ever found, predating other copies by almost 600 years. It seems that von Tischendorf told the monks that he wanted to “borrow” the manuscript so he could copy it. The generous monks believed him. Von Tischendorf made off with the manuscript to eventual worldwide fame. After publishing a facsimile of the valuable manuscript, von Tischendorf “loaned” it to the Tsar of Russia who had financed his trip. The Tsar took it as a gift.

The monks were wary of most visitors but they trusted a Quaker scholar named Rendel Harris. Harris had received a warm welcome at St. Catherine’s and he had been allowed to study a valuable work, a full text in Syriac called, “Apology of Aristides”. This find was important because it dated to early fourth century and proved once again that a completely developed Christian theology existed before the liberal scholars were willing to concede any developed Christian thought.

Secondly, while at St. Catherine’s Harris had been told about a dark closet off of a chamber beneath the archbishop’s rooms where more manuscripts were kept. He had not had a chance to look at them but he knew that Agnes and Margaret were planning a trip to Mount Sinai. After returning home from his own find, Rendel Harris rushed to Castlebrae, the twins’ home, and told them about his trip, his warm welcome by the monks, and what he suspected about the existence of other important manuscripts. He admired the twins and knew that they had the abilities necessary to be welcomed by the monks. He encouraged them in their dreams of visiting Sinai.

Thirdly, one of the reasons that Rendel Harris got along with the monks was because he could speak modern Greek. This impressed the monks and Rendel Harris knew that the ability to speak the language fluently would give the twins a warm welcome that could be refused to others. He also advised Agnes to brush up on Syriac so that she could positively identify the manuscripts that he believed were hidden away at St. Catherine’s. Agnes applied herself to learning this ancient language that was a variation of the Aramaic spoken by Jesus in the first century. God was getting this remarkable woman ready to identify one of the oldest copies of the Gospels in existence.

Fourthly, through her happy but brief marriage to the Cambridge scholar Samuel Lewis, Agnes was introduced into Cambridge society. She made many friends there. A traveler can’t just go waltzing into St. Catherine’s Monastery without letters of introduction and credentials. Agnes and Margaret were able to get an introductory letter from Cambridge and permission from the Archbishop in Cairo. This would not have been possible ten years before.

Fifthly, the sisters knew that they would not be able to take manuscripts away from the monastery. So these remarkably gifted women learned photography! They traveled with photographic equipment including 1000 film exposures. Later they would develop most of the pictures themselves. Again, God was preparing them to find and reveal the oldest copy of the Gospels then known to the world in the only way available at the time.

At last the day came for them to travel to Egypt. Ready now with command of Greek and Syriac, letters of introduction and permission, cameras, medicine, courage, and experience Agnes and Margaret set out to fulfill their dream of finding manuscripts that would prove that the Bible was written earlier than skeptics said.

When the sisters reached the monastery they were welcomed by the monks who had heard about them and were expecting them. The monks were delighted with these intelligent women who spoke perfect Greek. It also happened to be the custom of the monastery to welcome women pilgrims for their protection. The twins pitched their tents in the convent gardens and made friends with the monks. They began to work in the library the next day.

Agnes spotted a manuscript of dirty vellum. It seemed to be at first glance a collection of stories of women saints, but looking closer Agnes could see writing in columns underneath. This document was a “palimpsest”, containing pages where the old writing had been scraped down and new writing put on top. Agnes could see words such as “Of Matthew” and “of Luke” and realized that she was looking at possibly the oldest copy of the Gospels ever found. Agnes thanked the Lord for His providence in preparing her in every way to be the one to find this document.

Agnes and Margaret made photographic copies of their find and returned home. The Sinai Palimpsest (also called the Lewis Codex) proved to be from the fourth century. More remarkable still, it was a translation of a copy of the Gospels that dated to around 170 A.D. This was proof that Christianity was much older than the skeptics had said.

The scholars in Cambridge refused to acknowledge the find as significant. The sisters were ignored until scholars Robert Bensly and Francis Burkitt finally got a proper look at the photographs. They were excited and even frantic to get to the monastery to make a copy of the manuscript before anyone else could do it.

Agnes and Margaret put together another trip to Sinai with the three world famous scholars, Robert Bensly, Francis Burkitt, and their friend Rendel Harris and went back to St. Catherine’s to transcribe the manuscript. They were welcomed by the monks who gave them every assistance. When the work was finished the three returned home where most of the publicity centered around the sisters.

Agnes and Margaret were finally accepted into scholarly

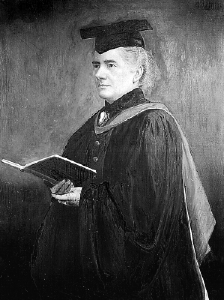

Agnes and Margaret were finally accepted into scholarly circles. They were denied degrees by Cambridge which did not grant women degrees until 1948, but other institutions were willing to honor the sisters as they should be. They received honorary degrees from St. Andrews and Heidelberg, Trinity College and Halle.

circles. They were denied degrees by Cambridge which did not grant women degrees until 1948, but other institutions were willing to honor the sisters as they should be. They received honorary degrees from St. Andrews and Heidelberg, Trinity College and Halle.

Agnes and Margaret went on traveling and exploring. The sisters were welcomed by professors for their expertise in ancient manuscripts. The twins were instrumental in the founding of Westminster College in 1899. Margaret died in 1920 and Agnes passed away in 1926. Agnes wrote several books describing their travels and especially the journey to Sinai to St. Catherine’s.

Even in our day the Bible is criticized as a work entirely of humans containing errors. Unbelievers are always looking for ways to ignore the fact that the Scriptures are the very Word of God. God has protected His Word over the centuries. How wonderful that he used two women to find a lost manuscript that would help boost the veracity of Christianity.

It is so ironic that the men at Cambridge refused to accept the testimony of Agnes Smith and Margaret Gibson because they were women. And yet, because they were women they were allowed to do what many men before them could not do. Because they were faithful women they were allowed to handle the manuscripts at St. Catherine’s and give a great gift to the world.

But God has chosen the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to shame the things which are strong… (I Corinthians 1:27)

*Soskice, Janet, The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels. (Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc., New York, 2010) page 126.