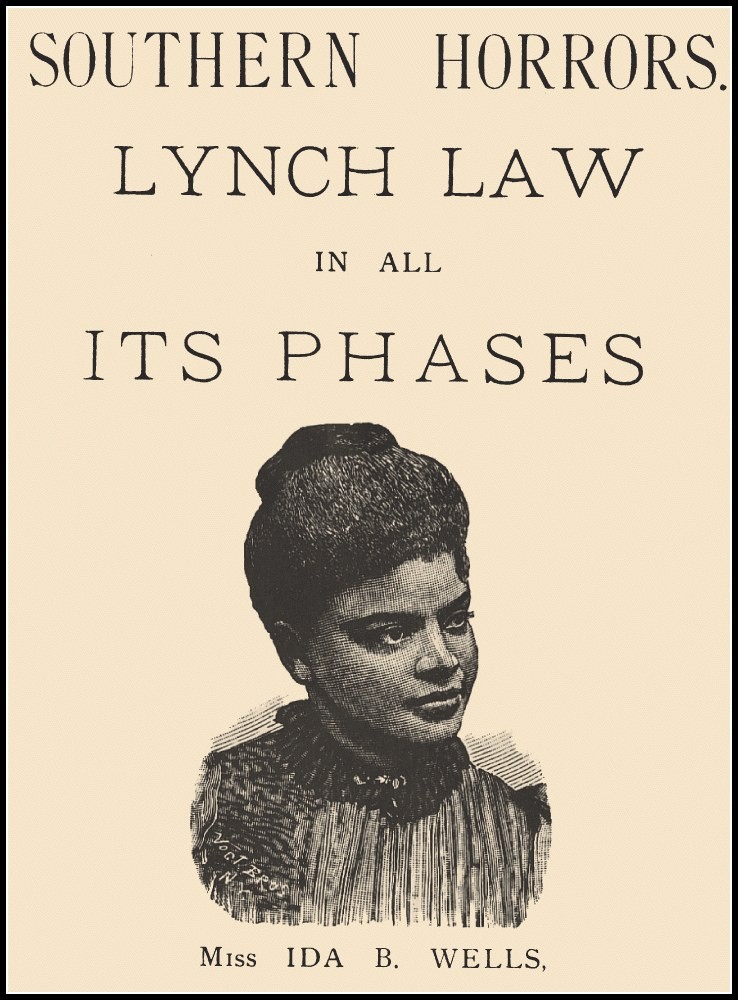

Ida Wells “understood the radical implications of her message and was prepared to endure the consequences even if, as she said, ‘the heavens might fall.’ But she had made up her mind that her campaign, wherever it took her, was her calling and that she would see it through. It was the determination of a woman who was indeed ‘dauntless,’ as the black press characterized her. It was also the determination of a woman whose campaign against lynching fit perfectly with her own leadership aspirations and emotional makeup. As a southerner-in-exile, she possessed an authority that gave her word more weight than those of northern leaders. The ‘outrage’ of lynching matched her inner storm; and the blood-libel horror of the crime gave Wells a wide berth of expression for her moral indignation and anger. Ida’s crusade to tell the truth about lynching gave her the means to reorder the world and her and the race’s place within it. Once defamed herself, now she would expose the lies that ‘sullied’ the race’s name and restore it. Somebody ‘must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning,’ wrote Wells, who had found the vehicle of her destiny, ‘and it seems to have fallen on me to do so.’” (Paula J. Giddings, Ida: A Sword Among Lions, pg. 229)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett has pretty much been forgotten today, but she was truly one of the bravest and most dedicated women who ever lived in America. She did not sit idly by when she saw the injustice that was being done to people of “color”. She met the challenge head on and I believe that black Americans came to enjoy more of their rights as citizens earlier than they otherwise would have because of her efforts.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett has pretty much been forgotten today, but she was truly one of the bravest and most dedicated women who ever lived in America. She did not sit idly by when she saw the injustice that was being done to people of “color”. She met the challenge head on and I believe that black Americans came to enjoy more of their rights as citizens earlier than they otherwise would have because of her efforts.

Ida was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi on July 16, 1862. She was the oldest daughter of James and Lizzie Wells who were slaves. After the War ended, James Wells helped to found a school for blacks. Ida attended this school until tragedy struck.

When Ida was 16 the yellow fever took the lives of both of her parents and one of her siblings. Ida dropped out of school to help take care of her younger sisters.

In 1882 Ida and her sisters moved to Memphis Tennessee to live with her aunt. Her older brothers had found work. Ida continued her education at Fisk University in Nashville.

A turning point came for Ida one day in 1884 when she was riding the train between Memphis and Nashville. She had bought a first class ticket and expected to use it. Train officials tried to make her sit in the African American car instead and she refused to move. The railway men physically removed her. Ida sued the railroad and won a settlement, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned it. Readers

in the African American car instead and she refused to move. The railway men physically removed her. Ida sued the railroad and won a settlement, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned it. Readers

may recall that in 1955, Rosa Parks refused to go to the back of a bus where the “colored” people were supposed to sit. Rosa went on to become an activist for equal rights for black citizens. Seventy years before this, Ida B. Wells became an activist in her own way.

Dauntless Ida picked up her pen and began to write about the injustices in the way blacks were treated. Her articles were published in black newspapers and periodicals. She was well received for her honesty and clear statement of the issues. Later Ida would be the owner of the Memphis Free Speech.

Another turning point came for Ida when a lynch mob murdered a good friend of Ida’s along with his two business partners. In 1892 Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart, African American men, were defending their store against an attack. They shot several attackers, white men. They were arrested, but before they could have the lawful trial that American citizens are entitled to, they were dragged out of their cells and taken a mile out of town to a railroad yard. The men were shot to death in a horrible fashion.

Ida wrote an editorial deploring the lynching in the Free Speech. Realizing that blacks were helpless against the white “mobocracy” she encouraged Negroes to save their money “and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.” In fact, many thousands did leave Memphis after this. In the late nineteenth century there weren’t many options for African Americans in cities that refused to give them their rights as citizens.

Ida had proven herself to be a good reporter and writer. With encouragement from friends, Ida traveled throughout the South and gathered stories and information about lynching. One thing that Ida was especially interested in was debunking the myths about the reasons for lynching. One common reason given for the lynching of black men was that they had raped a white woman. Ida gathered evidence that proved that while black men were the most common victims of lynching, black and white women and white men were lynched too. And there were many more reasons for lynching including prejudice, rioting, robbery, fraud, and incendiarism.

For example, in a speech given to a Chicago audience in 1900, Ida said that out of 241 persons lynched in 1892, 160 were of Negro descent. Not all were in the South; four were lynched in New York. Other victims included several children and five women.

For example, in a speech given to a Chicago audience in 1900, Ida said that out of 241 persons lynched in 1892, 160 were of Negro descent. Not all were in the South; four were lynched in New York. Other victims included several children and five women.

Ida also went on to report how horrible and full of hatred lynching was. Many times the bodies would be dismembered, riddled with bullets, or thrown into a fire.

Ida’s reporting was honest and must have been convicting because one day some whites in Memphis had had enough. They stormed the offices of Ida’s newspaper and destroyed all of her equipment. Fortunately, Ida was visiting in New York at the time. Her friends there warned her not to return to Memphis. Her life had been threatened.

This became another turning point in Ida’s life. She would not return to the South again for thirty years.

While in New York, Ida wrote “The Truth About Lynching”. She meant to wake people up and she did. Tens of thousands of copies were sold. Ida was hailed as a hero at the African American Press Association in Philadelphia.

But this was not enough for Ida. She got the press association to adopt a resolution to raise funds for an anti-lynching campaign. Money was needed for travel, publishing, and on-site investigations of the killings.

And so, while in exile in the North, Ida began her campaign against lynching. In Part Two, next week, we will continue her story. Besides fighting for justice Ida would know the joy of being a wife and mother. She would spearhead the founding of many organizations still with us today that help all Americans enjoy their God-given rights.