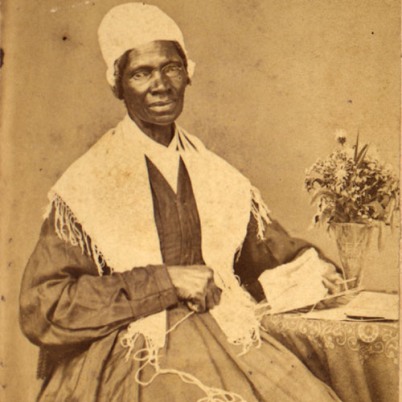

African-American Women in America – Sojourner Truth

For these few weeks we are covering the stories of many of the remarkable black women in the United States from the last several centuries. Life for black American women has taken many turns from slavery to emancipation. In spite of obtaining constitutional freedom, continued racism still affects black women economically, politically, and religiously.

Black women have a unique experience within evangelical Protestantism that is distinct even from black males and white females. Within black communities women are subject to male headship and so the black woman’s experience is different from that of black males. In effect black women belong to the lowest strata of society in the United States, behind white and black males and white women.

In spite of the prejudice against them, black females have practiced their Christian faith wholeheartedly. Many black women bravely follow their callings from the Holy Spirit to serve in the Church and society. From eighteenth century Philis Wheatley to twenty-first women today black women evangelists and preachers such as Jarena Lee, Sojourner Truth, and Amanda Berry Smith, Mother Eliza Davis George, Madam C. J. Walker, and Rosa Parks have made contributions in missions, business, and culture.

Last week we shared the story of the first black female writer to be published – the poet Philis Wheatley. We continue our series with an emancipated slave who became a black itinerant evangelist, abolitionist, women’s rights activist and writer – Sojourner Truth.

Sojourner Truth – (1797 – 1893)

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (Galatians 3:28).

The date of birth of Isabella Baumfree, whom we know as Sojourner Truth, is not certain but many think it was around 1797. She was born in Ulster County, New York to parents who were slaves. The state of New York did not give emancipation to the slaves until 1827, so Isabella Baumfree was a slave until her mature adulthood. Isabella had many last names over her lifetime, because she had a number of masters and it was common for slaves to take the last name of their master to show his ownership of them.

Isabella’s family lived on a Dutch plantation and she grew up speaking Dutch. At around age nine, she was sold to another family. They only spoke English and so there were frequent miscommunications. They beat her cruelly until she learned English, but she always spoke with a Dutch accent for the rest of her life.

She went through many trials until one day she finally ran away with her youngest daughter Sophia who was only an infant. Isabella had intended to stay with her owner until her emancipation, but he took advantage of her. He had promised her that he would free her one year before the New York law went into effect if she would render him faithful service until that time. When the time came, he reneged on his promise. She now faced one more year of harsh treatment. She was so angry that she determined to take what was justly her own.

She asked God to help her escape. She thought that she heard a voice telling her to leave in the early hours of the morning, so she did. Then she asked for direction and was given a vision of a house that she actually found later on her journey. There were some kindly Quakers living there. They invited her to stay. When her master caught up with her and tried to take her back, these kindly Christians, Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, paid the price of her last year’s service and so he went home with his $20. Isabella remained with these good people for a long time.

It was during this time that Isabella underwent a life changing experience. She had always had faith that God was real, but now she began to sense God’s overwhelming presence. She realized that Jesus had always loved her and her heart was so full of joy that she could not contemplate anything else except telling everyone what a wonderful Savior He is. A new life began for her.

At some point, Isabella wanted to change her name in order to leave behind all of the associations of her old life. She believed that the Lord gave her the new name of Sojourner. When asked why she changed her name she said it was because God had told her to travel east as a traveling preacher. She was now God’s instrument – a sojournerfor truth.

She had not troubled over having only a Christian name, but since it seemed good to have a surname she asked the Lord for help. “And it came in that moment, like a voice, just as true as God is true, ‘Sojourner Truth.’ And I leaped for joy. ‘Why,’ said I, ‘thank you, God; that is a good name. Thou art my last master, and thy name is Truth; and Truth shall be my abiding name till I die.'”[1]

Sojourner wanted to do something to help her people. Among other things she tried to get the United States government to give the colored people (as they were called in those days) some land out west. She believed that they could become self-supporting. This dream never materialized.

But Sojourner accomplished many other good things. Though remembered as an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, Sojourner also worked for prison reform, property rights and universal suffrage. She became a reformer in other ways. For example, due to the influence of the Quakers, she was concerned about how women dressed. We could use her advocacy today! She believed that modesty was more important than just blindly following the fashions. She had adopted Quaker style dress for herself. She was also an active worker in the temperance movement.

She was nearly six feet tall and strongly built. She had a deep voice and when she spoke people listened. She had been blessed with keen intelligence and common sense and was quick witted. She could debate opponents on issues point by point with irrefutable answers. One of her most famous speeches, which has been preserved for us is – “Ain’t I a Woman?” This was given at a women’s rights convention in Ohio in 1851. Here is a part of the speech as printed in the local paper at the time:

“And raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunders, she asked ‘And a’n’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at me! Look at my arm! (and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power). I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And a’n’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear de lash a well! And a’n’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen chilern, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And a’n’t I a woman?…….Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head; what dis dey call it?” (“Intellect,” whispered some one near.) “Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do wid womin’s rights or nigger’s rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?’ And she pointed her significant finger, and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud.

“If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder (and she glanced her eye over the platform) ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now dey is asking to do it, de men better let ’em.” Long-continued cheering greeted this. “Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now old Sojourner han’t got nothin’ more to say.”

Amid roars of applause, she returned to her corner, leaving more than one of us with streaming eyes, and hearts beating with gratitude.”

This was truly a remarkable speech allowing Sojourner to speak truth in a humorous way and avoid acrid criticism. She won many hearts with her wit and wisdom.

There are many other incidents that could be related about this fascinating woman. She is to be admired not only for her courage, but also for the way she rose above the inevitable harassment she received. One time she was told that the building where she was supposed to speak would be burned down. She responded, “Then I will speak to the ashes.” Her quick wit did not always protect her. After a violent mob physically assaulted her, her injuries to her leg were so severe that she always had to walk with a cane for the rest of her life.

Sojourner had no “book learning” but she was a power at meetings; there was no tongue more feared than hers. She did not accomplish as much for her people as she would have liked, but it was not her fault. Change was slow. Many other black women were freed and went on to poor or mediocre lives, but not Sojourner. “People ask me,” she once said, “how I came to live so long and keep my mind; and I tell them it is because I think of the great things of God; not the little things.”

Sojourner Truth died on November 26, 1883. Her last words were, “Be a follower of the Lord Jesus.” She accomplished many things but following the Lord Jesus was the most important to her. She was truly a remarkable woman.

[1]You can read more from her book: Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York, in 1828. (Boston: Printed for the Author. 1850). Available on many websites.