Is it possible for a woman to write the history of her family or ancestry without receiving criticism because she is a woman?

Is it possible for a woman to write the history of the congregation of the church that she attends without receiving criticism solely because she is a woman?

Now let’s suppose that a woman wants to write the history of the denomination of the church that she attends. Suppose there were things in the past that the members would rather not talk about. Perhaps there were one or two corrupt ministers in days gone by. Perhaps the church officials had rules that did not honor Christ or God’s Word. If this woman gives an honest account, should the book be rejected just because it was written by a woman? If a man wrote the same historical account, would it be acceptable?

“That’s ridiculous,” you might answer. “This is the twenty-first century. As long as a woman uses reliable resources and writes in a fair and balanced way, of course her book should be acceptable.”

You may be surprised to find that there are still many religious groups that will reject the writings of women that are about religious topics. That is a subject that I hope many readers will weigh in on.

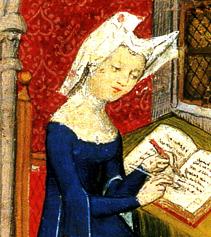

Be that as it may, certainly in the sixteenth century, women writers were not appreciated. There were many women who did write, however, and we respect them for their courage in following what they believed to be their call from God to contribute to the Reformation movement.

Marie Dentiere (1495-1561) was one of those writers. She was a Genevan Protestant reformer and a theologian in her own right. She played an active role in Genevan religion and politics, helping to close Geneva’s convents, and preaching and teaching with such reformers as John Calvin and William Farel. In addition to her writings on the history of the Reformation, she wrote to many influential people, such as Marguerite de Navarre.

Marie Dentiere (1495-1561) was one of those writers. She was a Genevan Protestant reformer and a theologian in her own right. She played an active role in Genevan religion and politics, helping to close Geneva’s convents, and preaching and teaching with such reformers as John Calvin and William Farel. In addition to her writings on the history of the Reformation, she wrote to many influential people, such as Marguerite de Navarre.

Marie wrote to give a history of the Reformation in Geneva and to defend the female perspective in the rapidly changing world. She believed that women could read and understand the Scriptures themselves, and coupled with the idea of the priesthood of all believers, women should be able to teach and spread the Gospel along with the men.

Much of Marie Dentière’s early life remains unknown. She was born into a relatively well-off family of nobility, and entered an Augustinian convent at a young age, eventually becoming abbess. However Martin Luther’s preaching against monasticism led her to leave the convent. She fled to Strasbourg to escape persecution–not only for abandoning her position as a nun but for converting to the Reformation. Strasbourg was a popular refuge for Protestants at that time.

While in Strasbourg, in 1528, she married Simon Robert, a young priest. Soon they left for an area outside of Geneva to preach the Reformation. They had five children together. Robert died 5 years later in 1533. Later, Marie married Antoine Froment, a follower of Calvin, who was at work in Geneva with Farel. Antoine Froment stood by Marie while she wrote her treatises and some believe even co-authored the first book.

Marie’s work stresses the importance of the Reformation, but also the need for a larger role for women in religious practice. To Marie, women and men were equally qualified and entitled to the interpretation of Scripture and practice of religion. In Geneva in 1536, she composed The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva. The work was published anonymously, and called for Genevans to adopt the Reformation. Kirsi Stjerna, in her book cited elsewhere on this Blog, calls her an early feminist. She says that Marie argued, as did women before her, that they were in the time of an emergency and it was necessary “for the benefit of the Christian faith for women to transgress the artificial boundaries set up by humankind.” (Stjerna, page 134) Did God raise up fervent, intelligent, courageous women at this time to aid in the spread of the true Gospel?

Nevertheless, Marie’s encouragement of female involvement in writing and theology angered the Genevan authorities. They arrested her publisher and destroyed as many of her books as they could. No other female writings were published in the city for the rest of the 16th century. This did not discourage her, and as a woman, she was criticized for her persistence and good works that a man would have been praised for. She and many other courageous women of the Reformation remained in obscurity for many years.

At last, centuries later, on November 3, 2002, her name was chiseled onto the “Wall of the Reformers”, one of the world’s principal monuments of the Protestant Reformation and one of the most visited sites in Geneva, a cradle of the Reformation. Marie took her place on the monument beside Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and other luminaries, finally getting the recognition she deserves for her part in the Reformation. Today, thank the Lord, some of her surviving writings are being found and published.

the Reformers”, one of the world’s principal monuments of the Protestant Reformation and one of the most visited sites in Geneva, a cradle of the Reformation. Marie took her place on the monument beside Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and other luminaries, finally getting the recognition she deserves for her part in the Reformation. Today, thank the Lord, some of her surviving writings are being found and published.

Note, however, what Marie said about the unusual times requiring unusual measures. Was God just using women in a special way at this time of tremendous change to help further the Reformation? Many women came to the aid of the Reformation, and even if some of them were neglected, their works helped spread the true Gospel to all of Europe. Have there been other times in history when this happened?

Getting back to the original question in this essay, should women be allowed to write on religious topics?

Just at special times?

Ever?