Marcella is best remembered as a disciple of the famous bishop, Jerome. She was born around 325 AD and lived to the ripe old age of 85. The anniversary of her death on January 31, 410 AD, is still observed in the Catholic Church. She was a gifted biblical scholar. Having been born into a wealthy family, her social position allowed her to deepen her spiritual life due to the education she was able to receive. She was instructed in Greek and Hebrew and loved to study the Scriptures. She was devoted to Christ all of her life, and when she was widowed, she established a religious community.

around 325 AD and lived to the ripe old age of 85. The anniversary of her death on January 31, 410 AD, is still observed in the Catholic Church. She was a gifted biblical scholar. Having been born into a wealthy family, her social position allowed her to deepen her spiritual life due to the education she was able to receive. She was instructed in Greek and Hebrew and loved to study the Scriptures. She was devoted to Christ all of her life, and when she was widowed, she established a religious community.

As a small girl Marcella heard Saint Athanasius speak. His stories of the Desert Fathers of Egypt enthralled her, planting deep in her heart the seeds of a future marked by asceticism and devotion to the Word of God. Athanasius gave her a copy of his Life of Antony, the hermit-monk who did so much to make monasticism a major force in Christianity during those centuries. Antony’s ascetic practices greatly impressed Marcella. Later, thanks to early widowhood and a great inheritance, she would establish a monastery for women on her own.

Marcella married at around age 17, but was widowed after only seven months. Her husband’s death left her independently wealthy. She resisted the social pressure to remarry. When an elderly Roman consul, Cerealis, proposed to leave her all his money if she would marry him, Marcella replied, “If I wished to marry, I should look for a husband, not an inheritance.” Her mother was disappointed, but Marcella had a mind of her own.

This young widow turned her home into an academy for the study of Sacred Scripture and a school of prayer. A devout contemporary of hers, Paula, and other Roman ladies, eager for the pursuit of holiness, joined her. These women gave much of their money to the poor. Marcella distributed her considerable wealth, “preferring to store her money in the stomachs of the needy rather than hide it in a purse.”

Marcella changed her dress from that of a woman of position to the plainest and coarsest of garments. She dressed modestly, with an aim to hide her dazzling beauty. This was in contrast, says Jerome, with the usual “widow’s weeds”, which aimed to attract men and to gain another husband.

Marcella spent her days in study, in visits to the churches of the martyrs, in prayer, and in good works. She gathered around her a circle of like-minded women, and Jerome says that she educated Eustochium, the youngest of Paula’s children, another female scholar. Marcella’s example, asserts Jerome, was responsible for the growth of monasteries in Rome, where the number of such houses began to rival the number in Jerusalem.

Marcella had a very brilliant mind. Most of what we know about this rare woman comes  from letters of Jerome. Marcella met and studied with this great scholar (who made the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible). The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, exchanging thoughts on many issues, such as the Montanist heresy or the sin against the Holy Ghost. Marcella probed Jerome with pertinent questions. More than once she challenged him with difficult and subtle questions concerning the Scriptures. It was for Marcella that Saint Jerome wrote his explanation of the Hebrew words Amen and Alleluia.

from letters of Jerome. Marcella met and studied with this great scholar (who made the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible). The two corresponded for the rest of their lives, exchanging thoughts on many issues, such as the Montanist heresy or the sin against the Holy Ghost. Marcella probed Jerome with pertinent questions. More than once she challenged him with difficult and subtle questions concerning the Scriptures. It was for Marcella that Saint Jerome wrote his explanation of the Hebrew words Amen and Alleluia.

In a letter to the Roman lady Principia, who was Marcella’s pupil, Jerome compares Marcella to the prophetess Anna in Saint Luke’s Gospel. “Let us then compare her case with that of Marcella,” he says, “and we shall see that the latter has every way the advantage. Anna lived with her husband seven years; Marcella seven months. Anna only hoped for Christ; Marcella held Him fast. Anna confessed Him at His birth; Marcella believed in Him crucified. Anna did not deny the Child; Marcella rejoiced in the Man as king.” This is Jerome’s spiritual portrait of Marcella: she clung to Christ, believed in Him crucified, and rejoiced in Him as King.

While Jerome praises Marcella for her virtue and intelligence, he also tells her spiritual daughter, Principia, that Marcella did not accept blindly his scriptural exegeses but argued with them. She asked questions to learn more. She took in quickly what he had gained through long study. Because he valued her comments, he continued to submit his work to her judgment before he made them public. He adds that she frequently rebuked him for his hasty temper.

Several of Jerome’s letters to Marcella survive and are well worth reading. Among the sayings of Marcella, one comes from the period in her life when a humiliated Rome was in the throes of a famine and Marcella herself was languishing after having been turned out of her own home. She was eighty-five at the time, and she said: “By heaven’s grace, captivity has found me a poor woman, not made me one. Now, I shall go in want of daily bread, but I shall not feel hunger since I am full of Christ.”

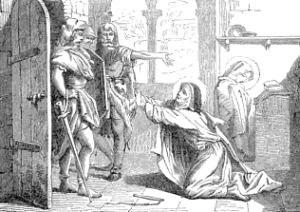

When Alaric of the Goths seized and sacked Rome in 410, soldiers from his army invaded Marcella’s mansion on the Avertine Hill in the hopes of gaining her treasure. His troops gathered as much booty as they could, but it was much less than they were expecting. Marcella was tortured to reveal where her supposed wealth was hidden. She showed them her coarse dress, insisting truthfully that she had given everything away. Forgetting about her own sufferings, she pleaded that the soldiers not rape Principia, her pupil. The soldiers finally took her to a church, where she died praising God.

Marcella’s mansion on the Avertine Hill in the hopes of gaining her treasure. His troops gathered as much booty as they could, but it was much less than they were expecting. Marcella was tortured to reveal where her supposed wealth was hidden. She showed them her coarse dress, insisting truthfully that she had given everything away. Forgetting about her own sufferings, she pleaded that the soldiers not rape Principia, her pupil. The soldiers finally took her to a church, where she died praising God.

Today, when we study church history, much mention is made of Jerome. Scholars have apparently decided to overlook the life of Marcella, a woman who was praised in many letters by Jerome. She was a noble woman whose wealth allowed her education and alms-giving. She was a leader in Christian Rome, much in accordance with her social rank. Her love of Christ, however, led her to voluntary poverty and courageous martyrdom. We would do well to learn from her example as a determined, single-minded woman, who only wanted to spend her whole life studying about Christ and imitating His example to serve the poor.