The wonder of it, which will grow, I think, more and more through the eternal ages, is that God should allow us, his poor creatures, to share with him in a work far greater than the creation of a universe, even the founding of an eternal and limitless kingdom of holiness, glory and peace. Lillias Underwood*

Lillias Horton Underwood was one of the countless numbers of courageous women who went to serve on the mission field in spite of the dangers. Women who went to places like Africa or the Orient in the nineteenth century were warned that they would return in a coffin. Lillias trusted God and ventured into the interior of Korea as the first white woman ever to do so.

Lillias Horton Underwood was one of the countless numbers of courageous women who went to serve on the mission field in spite of the dangers. Women who went to places like Africa or the Orient in the nineteenth century were warned that they would return in a coffin. Lillias trusted God and ventured into the interior of Korea as the first white woman ever to do so.

Lillias was born on June 21, 1851 in Albany New York. She went to Chicago to the Women’s Medical College (now a part of Northwestern University) to obtain a medical degree. After graduation she worked at Mary Thompson’s Hospital. It was here that the Presbyterian Mission approached Lillias about serving in Korea.

Miss Lillias Horton went to Korea as a medical missionary in 1888. Though an unmarried woman and alone she was not helpless. She maintained a cheerful attitude and went about her work at the missionary hospital efficiently and enthusiastically. Once she had consecrated her life to serving Christ on the mission field she never looked back. She felt the importance of healing the bodies and enlightening the souls of the poor and destitute to be a life-time and a life-fulfilling call. She had completely sold out to her Lord Jesus Christ.

Not long after her arrival in Chemulpo Korea, Lillias visited the queen who desired to secure the services of Lillias as her personal physician. Lillias and Queen Min would maintain a warm friendship until the cruel assassination of Queen Min in 1895. Lillias described Queen Min as intelligent, warm, an excellent diplomat, and devoted to the welfare of her people. The queen was of a higher mind and morals than the king and was his royal counselor. It was well known that she was the strength behind the throne.

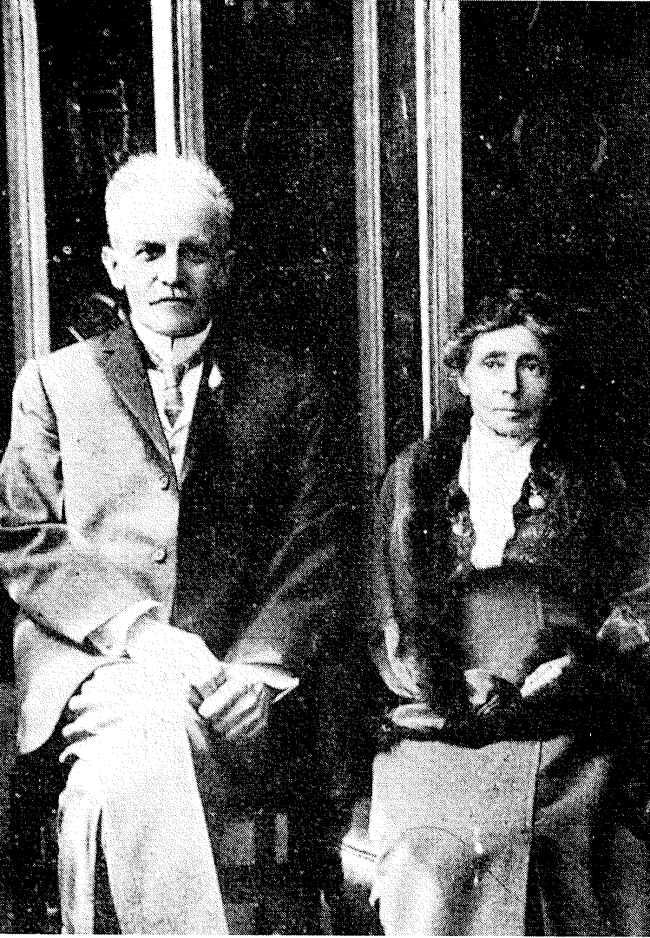

In 1889 Lillias married Reverend Horace G. Underwood. Horace had already been in Korea for four years and knew how to arrange the trips through dangerous territory. He arranged their honeymoon consisting of a trip to the northern part of Korea where few white men had ever been seen and no white women. Most women might have complained about this kind of honeymoon but Lillias said that she was not in Korea to be a tourist in pursuit of entertainment, but she was an ambassador of Christ.

four years and knew how to arrange the trips through dangerous territory. He arranged their honeymoon consisting of a trip to the northern part of Korea where few white men had ever been seen and no white women. Most women might have complained about this kind of honeymoon but Lillias said that she was not in Korea to be a tourist in pursuit of entertainment, but she was an ambassador of Christ.

Though most foreigners were distrusted in Korea, the Underwoods impressed the Korean officials and were allowed to take a journey to the far north. They traveled as missionaries without disguise. It was a “plucky undertaking for the young bride, since, so far as known, she was the first foreign woman who had made such a tour. The journey was a protracted one and involved all kinds of hardship and privation. Nothing worthy of a name of inn was to be found, but only some larger huts in which travelers were packed away amid every variety of filth and vermin.” *

We have read many stories of missionaries who gained the trust of the officials in foreign countries because of their service to them. How often have we heard how a formerly antagonistic ruler changed his mind when the medical missionary healed that chief’s wife or son or daughter? The situation in Korea was similar. God used the first medical missionary to Korea, Dr. H. N. Allen to open the door to missions when Dr. Allen healed the wounds of some distinguished Koreans.

And so the Underwoods had permission to travel to northern Korea. With her unfailing good nature Lillias described how the natives would make holes in the paper doors and windows to get a glimpse of the only white woman they had ever seen. This ruined any chance of privacy that Lillias might have had, but she endured “these rude intrusions into my privacy with more sang froid, excusing and understanding it.”*

After this trip the Underwoods returned to Chemulpo. They continued their work at the mission. Lillias was in charge of the Women’s Department at the Government Hospital (Chejung-won) as well as the English and arithmetic teacher for the boys’ orphanage founded by Horace Underwood. She led Sunday school classes for boys and Bible studies for women.

The Underwood’s had one child, a son born in 1890. Horace Horton Underwood would return to Korea as a missionary after graduating from New York University. He would serve until his death in 1951 in Pusan.

Lillias sacrificed all of the comforts of home in America, but she took care of herself. Her wisdom in doing this would pay off. One missionary sacrificed his own health out of love for the poor. The mission sent him healthy food that he promptly gave away to the hungry Koreans. His zeal led to his early death. Lillias admired his great love and sacrifice yet she wondered whether he had not died too early. Surely if he “could have gone on living and preaching, as they might, had they been able to mix with their enthusiasm and consecration, wisdom and temperance” more work could have been accomplished. Lillias maintained the balance between sacrifice and wisdom.

Because of the many invasions by foreign enemies King Gojong’s reign was precarious. He had signed unwise treaties with the Japanese giving them control of much of Korea against Queen Min’s advice. (As we know, the Japanese would dominate Korea until 1945. See a related story on this blog about Ahn Ei Sook, published April 22, 2010.)

In 1894 thousands of Korean peasants were slaughtered by the Japanese. Queen Min tried to get the Russians to come to their aid. Angry that the queen might be able to do something to save her people, the Japanese formed a plot to assassinate her. The Japanese brutally murdered her. The king was held a virtual prisoner in the palace while a group of men sympathetic to the Japanese took over.

In 1894 thousands of Korean peasants were slaughtered by the Japanese. Queen Min tried to get the Russians to come to their aid. Angry that the queen might be able to do something to save her people, the Japanese formed a plot to assassinate her. The Japanese brutally murdered her. The king was held a virtual prisoner in the palace while a group of men sympathetic to the Japanese took over.

Despite the grave risks to their lives from disease, marauders, and the uncertain political situation, Horace and Lillias remained in Korea until Horace’s failing health forced them to return to the U.S. After his death, Lillias returned to Korea with Horace Hornton and his new wife. Lillias retired from medicine and continued missionary work.

Lillias wrote “Fifteen Years Among the Top-Knots, or Life in Korea” published in 1904 and in 1908. She also wrote a biography of her husband, “Underwood of Korea” (1918). These few details of her life given in this blog story are just a taste of her narrative of life among the “top-knots”, so called because of the way they wore their hair in a knot on top of their heads. This book is very engaging and you will be amazed at the love of the Underwood’s as they serve the Koreans. (It is available as a free download on the internet. Go get it; you won’t be sorry.)

1908. She also wrote a biography of her husband, “Underwood of Korea” (1918). These few details of her life given in this blog story are just a taste of her narrative of life among the “top-knots”, so called because of the way they wore their hair in a knot on top of their heads. This book is very engaging and you will be amazed at the love of the Underwood’s as they serve the Koreans. (It is available as a free download on the internet. Go get it; you won’t be sorry.)

*From “Fifteen Years Among the Top-Knots” by Lillias Underwood