Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country.

Moments later the German firing squad took the life of the brave nurse, Edith Cavell.

Edith Cavell (1865 – 1915) was a British nurse operating a small nursing school in Belgium, which she started in 1907. Then World War One started, and the Germans occupied Belgium in 1914. Edith joined the Red Cross and converted the school into a hospital and cared for wounded soldiers of all nationalities, even those of the occupying army of Germany.

Belgium, which she started in 1907. Then World War One started, and the Germans occupied Belgium in 1914. Edith joined the Red Cross and converted the school into a hospital and cared for wounded soldiers of all nationalities, even those of the occupying army of Germany.

“It is our duty as nurses,” Edith said to the young women, “to care for all of the wounded, no matter from what nation they come.” Some of the nurses did not want to help the hated Germans, but Edith reminded them, “The Lord Jesus said to love your enemies and do good to those who hate you.” Edith believed that the profession of nursing should go beyond political and national boundaries. Certainly, the love of Christ should be shared with all.

Some may disagree with Edith, thinking that she should have just given up the school and gone back to England. But Edith was passionate about helping others.

Edith had grown up in a small town in England called Swardeston. She was the daughter of an Anglican minister. As a child, she learned the valuable lesson of helping others. There were many poor people in Swardeston and Edith often took baskets of food to them. One Sunday, her father preached from the gospel of Matthew, “And whoever in the name of a disciple gives to one of these little ones even a cup of cold water to drink, truly I say to you, he shall not lose his reward.” This sermon had a great effect on Edith; she would never forget it. Her father said, “You must also remember that some day you may be on the receiving end. You might be reduced to such straits as to be glad of a cup of cold water. You might be sick, friendless, alone somewhere where you feel absolutely forsaken. But remember that you will never be so alone that God is not there . . “ Edith would have reason to be thankful for this encouragement later.

While Edith was running her hospital in German occupied Brussels, some Belgian patriots came to her and asked her to treat some wounded Allied soldiers. This would be dangerous for her, but she agreed. She hid them in some separate rooms and cared for them. Later, she helped them to escape to Holland, which was a neutral country. Over the course of the next year Edith aided hundreds of Allies in their escape from Belgium.

While Edith was running her hospital in German occupied Brussels, some Belgian patriots came to her and asked her to treat some wounded Allied soldiers. This would be dangerous for her, but she agreed. She hid them in some separate rooms and cared for them. Later, she helped them to escape to Holland, which was a neutral country. Over the course of the next year Edith aided hundreds of Allies in their escape from Belgium.

The German secret police were watching her hospital closely in the summer of 1915, and finally on August 5, she was arrested. She was kept in solitary confinement for nine weeks. At this time a few friends brought her small baskets of food once a week. She remembered her father’s words so many years ago. Now she was on the receiving end. And she knew that God would be with her. As she stared at the four walls of her small cell, she knew that she was not alone.

The German authorities interrogated Edith repeatedly. Finally, one day, after getting nowhere with their questioning, the interrogators tricked Edith. They told her that they already had the necessary information and that she could only save her friends from execution, if she made a full confession. Edith was always a truthful woman, and she believed the best about others. Edith trusted her interrogators and made a full confession. In fact, the only evidence they had was one postcard from a soldier thanking her for her help while he was in Brussels. The German authorities were ecstatic having obtained her confession.

A trial began on October 7, 1915. It lasted only two days. On Sunday, October 10, sentence was pronounced. The Germans were in a hurry to carry out the sentence against Edith. There was pressure from the American and Spanish ambassadors to limit her sentence to imprisonment. They stressed the fair way that she had treated all soldiers, including Germans. They reminded them that she was not a traitor, because she was not a German citizen. All of this fell on deaf ears. The German authorities fixed the date for her execution on October 12, 1915. Edith accepted her fate. She told the English chaplain in Brussels, Stirling Gahan, who visited her the night before her death, “And now, standing in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred towards anyone”.

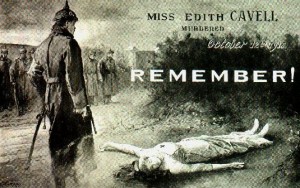

At dawn on October 12, Edith was executed by firing squad at the National Rifle Range located on the outskirts of Brussels. She was buried nearby. A German military chaplain was with her at the end. Afterwards he gave her a Christian burial. He said, “She was brave and bright to the last. She professed her Christian faith and that she was glad to die for her country. She died like a heroine.”

After the war ended, her coffin was exhumed and taken back to England. A state funeral was held in Westminster Abbey on May 15, 1919, but her family wanted her to be buried near Norwich Cathedral, which was not far from her home in Swardeston. She is buried in Life’s Green, close to a WWI memorial. A service, attended by many visitors, is held at her graveside every October, on the nearest Sunday to the date of her death.

Although the Germans thought that her death would deter others from helping Allied soldiers, their actions backfired on them. Within days of her shooting, Edith had become a heroine. She was viewed as a martyr, giving her life for others. Her execution strengthened Allied morale. British, Canadian, and Australian men lined up to enlist at the recruiting stations.

soldiers, their actions backfired on them. Within days of her shooting, Edith had become a heroine. She was viewed as a martyr, giving her life for others. Her execution strengthened Allied morale. British, Canadian, and Australian men lined up to enlist at the recruiting stations.

Another outcome of her death was that many other lives were saved. There was a worldwide storm of protest over her execution. The Germans decided to spare the lives of 33 other prisoners.

When she was a child, Edith’s father prayed with her that she would grow up to serve God in some special way. She certainly did this. Her life shows how a woman of faithfulness and courage trusts in God for protection and guidance. She was not afraid of death. She said to the chaplain who visited her the night before, “We shall meet again.” I am looking forward to meeting Edith myself.