During this last summer we have been relating the stories of remarkable black women of the nineteenth century. Some were born as slaves and some were born free. All of these women were courageous examples of what can be done by a woman who does not let her circumstances dictate to her. These women rose above many hardships including poverty, illness, prejudice, internal conflicts, and the limitations of their times to follow their call from God and affect the lives of many other people for good. Why were they able to live in a realm above their circumstances? It is because they all received strength from God. They all answered the call in their lives to serve.

We covered the stories of remarkable female activists and preachers – Philis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, Jarena Lee, Zilpha Elaw, and Julia A. J. Foote. Some of these gifted women also bequeathed to us their very fine autobiographies. It was acceptable for women to write and so many availed themselves of the opportunity to express themselves using this medium. It is exciting to read about events from that century told from a personal point of view. The women wrote about their thoughts, dreams, and ideas that they could not express publicly because of their gender or color. We thank God for their efforts.

This fall we will continue with the stories of more black women in the kingdom of God in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In spite of the limitations they had imposed on them by society these women rose above their circumstances to become evangelists, missionaries, journalists, business women (one was a bank president!), philanthropists, teachers, and activists.

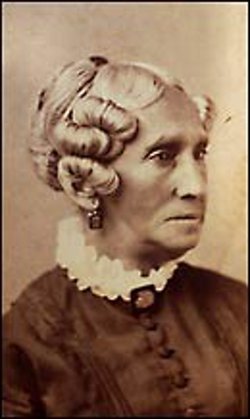

Maria Stewart (1803-1879) – Teacher, Activist, Writer

Is not my word like as a fire? saith the Lord; and like a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?” Jeremiah 23:29

Not until many years after her death was Maria W. Stewart recognized as an underappreciated black female theologian and speaker of the early nineteenth century.

She is believed to be the first American woman to have given a speech before a mixed audience of men and women. It is possible that there were other women speakers before her, but we don’t have copies of their speeches as we do for Maria.

Maria Miller was born in 1803 in Hartford, Connecticut. Other than their last name, we don’t really know anything about Maria’s parents. She was orphaned at the age of five and became a servant girl in the home of a minister. While there she learned to read and became very familiar with the Bible. She understood it so well in fact that one she would later incorporate it into her speeches in very intelligent and appropriate ways.

At about age fifteen, Maria left this family and took a job as a domestic servant in order to support herself. She further educated herself by attending Sabbath schools.

When she was twenty-three, Maria Miller married James W. Stewart at the African Baptist Church in Boston. Maria took not only James’ last name but also his middle initial and thereafter she called herself Maria W. Stewart. James was forty-four years old. He was a veteran of the War of 1812. When he and Maria married he was a successful businessman earning a good income by outfitting whaling ships and fishing vessels. At this time, blacks or colored persons (as they were called then) made up only three percent of the Boston population. The Stewarts were also members of an even smaller society – the black middle class. They had no children and James died only three years later in 1829.

Heartbreak helped to fuel Maria’s zeal for God and His Word and freedom for women and blacks. But first, before she started her remarkable foray into politics, Maria had to try and get her inheritance. James Stewart had left her substantial property, but she was defrauded by the legal machinations of the unscrupulous white businessmen who were the executors of the estate. After a long court battle they took everything from her.

In 1830 Maria underwent a religious conversion that led her to begin to proclaim the Gospel along with social justice. She made a public profession of her faith in Christ and dedicated herself to God’s service. Being black and female did not stop this remarkable woman. She believed that the Scriptures were the authority of God and she could proclaim them as a servant of God no matter what her gender was. She also believed that it was an act of obedience to God to work for freedom for oppressed people. Throughout her life she would be criticized for speaking out, but Maria would point to the authority of God and say that she was simply following God’s will. This was an incredibly bold stance for a black woman to take in 1830. It would be a few years before other women would follow in her footsteps and now there is a great “roll call” of black and white women who boldly proclaimed the Word of God.

Maria’s first published work was entitled, “Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build”. This appeared as a twelve-page pamphlet, priced at six cents, published in 1831. Soon after this, Maria began her public speaking.

The main thrust of Maria’s speeches was to encourage black women to turn to God. She also urged them to stand up for their rights and not remain silent. She showed that free black women were little better off than the slaves. The only employment they could get was as servants to white people and many were as mistreated as she was. After all, she should know because she was cheated out of her inheritance. Being black and female was the bottom of the social hierarchy.

While speaking out against the unfairness of the white man’s world, Maria also boldly lectured the blacks themselves for doing little to better their own plight. “It is useless for us any longer to sit with our hands folded, reproaching the whites; for that will never elevate us,” she said.

Maria continued to write articles for publication. In 1832, the famous publisher William Lloyd Garrison published another article entitled, “Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart.” He also printed transcripts from all of her speeches, but going along with the social requirements of those days he put them in the “Ladies” Department” of the paper.

Maria Stewart continued to speak and write for only two more years. She had encountered so much opposition that she decided to leave Boston. She delivered her last speech on September 21, 1833 announcing her decision. She was truly sorry that even people who agreed with her did not like her speaking in public.

She did not just fade away. Maria refused to go quietly, asserting that women activists had divine sanction: “What if I am woman; is not the God of ancient times the God of these modern days? Did he not raise up Deborah, to be a mother, and a judge in Israel? Did not Queen Esther save the lives of the Jews? And Mary Magdalene first declare the resurrection of Christ from the dead?”

Maria moved to New York where she became a teacher and taught in Manhattan public schools. She continued her political activities, joining many women’s organizations. She did lecture occasionally, but none of these have survived.

In 1852, Maria moved to Baltimore. Here she earned a living as a teacher. In 1861, she moved to Washington D. C. where she operated a school. By the 1870’s she had been appointed a matron at the Freedman’s Hospital and Asylum in Washington. Maria continued to teach even as she worked at the hospital caring for patients.

Finally, in 1878, a year before her death, congress passed a law granting pensions to widows of veterans of the War of 1812. (Big of them, wasn’t it? How many widows could there be sixty-six years after the end of the war?) Anyway, this money enabled Maria to publish a second edition of “Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart”. It also included new sections, an autobiographical essay and an introduction calling for an end to tyranny and oppression of underprivileged peoples.

Maria died in 1879 at the Freedman’s Hospital at the age of 76. There was an obituary in The People’s Advocate, giving this recognition to Maria Stewart: “Few, very few know of the remarkable career of this woman whose life has just drawn to a close. For half a century she was engaged in the work of elevating her race by lectures, teaching, and various missionary and benevolent labors.” Maria was buried in Graceland Cemetery in Washington on December 17, 1879—50 years to the day after her husband’s death.