February is Black History Month. In our first post this month (February 1, 2019) we reviewed the book, Sisters of the Spirit: Three Black Women’s Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century. The book contains the writings of three black women who have been forgotten but were well-known in their day. Thousands of people came to Christ thanks to their preaching and teaching.

For several weeks this month we are looking more closely at each of the three women’s stories and their writings. We began with Jarena Lee (1783 – 1864), who was born to free but poor black parents. She was the first African American woman to give us an account of her religious experiences. Last week we looked at the remarkable life of Zilpha Elaw (1790-??) who traveled to many states preaching the gospel.

In this post we will look at the life of Julia A. J. Foote (1823-1900) including excerpts from her biography. I think you would enjoy reading the whole book, Sisters of the Spirit because it demonstrates that women are called and gifted by the Holy Spirit to preach the gospel. You will see from all of the women’s very frank accounts of their lives that they struggled with accepting their call. Women, especially black women, were not considered fit for this kind of kingdom work for God. The true stories of Jarena Lee, Zilpha Elaw, and Julia Foote will show that God does indeed call and gift women for service.

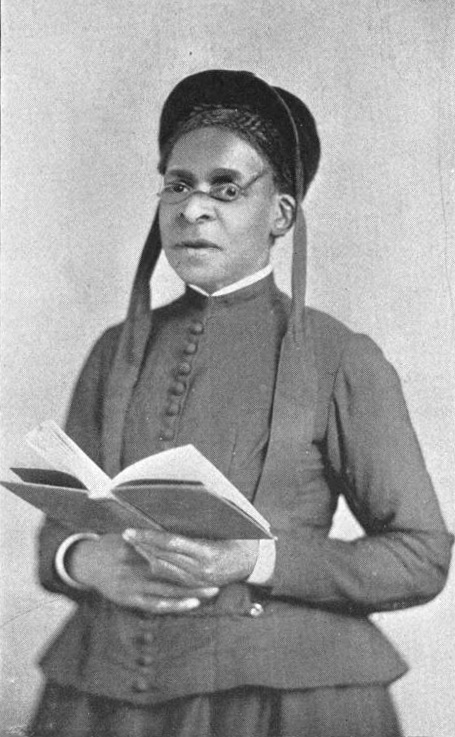

Julia A. J. Foote

Is not this a brand plucked out of the fire?(Zechariah 3:2).

In the past few weeks we have told the stories of remarkable black women of the nineteenth century. Some were born slaves and some were born free. All of these women were courageous examples of what can be done by a woman who does not let her circumstances dictate to her. These women rose above many hardships including poverty, illness, prejudice, internal conflicts, and the limitations of their times to follow their call from God and affect the lives of many other people for good.

During the nineteenth century many black and white women published their autobiographies. There are also many fine diaries from that century when women wrote about their thoughts, dreams, and ideas that they could not express publicly because of their gender. It was acceptable for women to write and so many availed themselves of the opportunity to express themselves using this medium.

An outstanding example of such a woman was Julia A. J. Foote (1823-1900). Julia Foote intended to leave her story so that she could “testify more extensively to the sufficiency of the blood of Jesus Christ to save from all sin.” Her autobiography was published in 1879.

She was born in 1823 in Schenectady, N.Y., a child of former slaves. Her mother had been born a slave; her father was born free but was kidnapped and enslaved as a child. Julia’s father endured many hardships but worked hard and purchased his freedom along with that of his wife and their only child at that time.

A nearly fatal accident for Julia’s mother caused her parents to turn to God and they became committed Methodists. Julia’s parents wanted their children to be educated, but the schools were segregated, so they sent Julia to work as a servant and the white family she lived with used their influence to put her in a country school. Julia wanted to read the Bible and so she studied hard in school and learned to read.

Julia attended many church meetings and was converted at age fifteen. Her experience was very profound and left her with a strong desire to serve Christ for the rest of her life. It also left her with a desire to be holy. She eventually embraced the Methodist idea of “sanctification”. This doctrine has been debated for centuries, but some Methodists believed in “total sanctification” where one is freed from sin completely and empowered to lead a life of spiritual perfection. Most Christians believe that sanctification is a gradual process, the Christian becoming more Christ-like as the years go on, and only becoming “perfect” when they die and go to heaven. Julia believed that absolute perfection belonged to God alone. However, Christian “perfection” was moving toward a life of love and peace with God. This Julia strove to do.

In 1841, Julia married George Foote, who was a sailor, and moved to Boston with him. There she joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church. She made friends and studied the Bible. Convinced that she was fully sanctified by the Holy Spirit, she also believed that she was called to preach. When she tried to tell others, including her husband, she met with disapproval. It was all right for her to work with the neighborhood wives and children, but as a woman she was not supposed to speak in public.

Julia had always been opposed to women preaching and had spoken out against it, but she began to have strong feelings toward preaching the Gospel and seeing many people come to Christ. God seemed to be calling her, but she felt unworthy of the task and said, “No, Lord, not me.” The impression that God was calling her increased daily, yet she tried to shrink from it. One day she received a visitation from an angel who told her that she was to go and preach the Gospel. She tried to shirk this call for two months and became very sick. Her friends advised her to obey God. When she got well, Julia realized that God had been gracious to her. God sent another angel and this time, Julia bowed her head and said, “I will go, Lord.”

Julia met with opposition from her minister when she explained her divine calling to him. She and other like-minded brothers and sisters began to meet in her home. She was told to quit these meetings or else face discipline. She responded that she had to obey God, and she was turned out of her church.

There were other heartaches for Julia. Her husband did not agree with her and drifted away from her, literally, as he spent most of his time at sea, eventually dying there. Her parents did not approve of her activity, but her father gave her his blessing on his death bed saying to her, “My dear daughter, be faithful to your heavenly calling, and fear not to preach full salvation.”

Of course, there were the “indignities” that were shown to her as a “nigger”. All of these things Julia endured as she went about the work of her Master.

A Christian sister joined her as her traveling companion and they went throughout New England, the Mid-Atlantic States, Michigan, Ohio, and Canada. Julia was welcomed in Churches, homes, and revival camps. She was part of the holiness revivals that swept through the Midwest in the 1870’s. Julia served as a missionary for the A.M.E. Zion Church.

We are not sure what she was doing during the 1880’s and early 1890’s, but by the end of the last decade of the nineteenth century, Julia became the first woman to be ordained a deacon in her church. Later she became only the second woman to hold the office of elder. Julia died around 1900 after sixty years of ministry.

Julia protested against racism and other social abuses during her lifetime. Her special cause however was to encourage her Christian sisters to serve God in spite of their gender or color. Though slavery was long ended by the time she died, there was still much prejudice against blacks. Julia encouraged all believers to remember that God “made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth ” (Acts 17:26). There is no room for prejudice among Christians.

All Christians have the responsibility to tell others about the love of Christ. Julia believed that women could be anointed to preach publicly because “there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). God’s praise should be on everyone’s lips!

Those who heard Julia preach believed that she had the gift and the anointing of the Holy Spirit as she spoke with such power. At one meeting there were over five thousand people listening intently as she explained the way of salvation. Other ministers attested to the soundness of her doctrine and exhortation and commended her for it.

Julia was faithful to her calling. She was grateful for her redemption, “a brand plucked out of the fire” and her life has been an inspiration for Christian women since then.

Julia’s story is one of three stories of remarkable black women preachers from the nineteenth century. God called and gifted these women for service in His kingdom. Many, many more women have served in the last few centuries in the United States. It is tragic that their stories have been all but forgotten.

Next week we will continue with another story about an early nineteenth century black female preacher – Maria W. Stewart. (Her story is found in Black Women in Nineteenth Century American Life. To be reviewed next week).