One of the really great women of courage, compassion, and determination was Elizabeth Gurney Fry. Most people remember her chiefly for the prison reforms that she helped bring about in the nineteenth century in England. But, Elizabeth went beyond her work at Newgate prison and became active in reform for mental asylums, the convict ship system, nursing standards, education for working women, better housing for the poor including hostels for the homeless, and she founded soup kitchens.

She did all of this on top of being an active and devoted mother of eleven children, Bible teacher for the children in her neighborhood, and a sometime minister in her local Quaker congregation.

There is so much to admire about this woman, but in this essay I would like to focus on her work in the prisons. How was she able to accomplish so much?

Elizabeth had been born the third child out of twelve in a Quaker (Society of Friends) family, in 1780. Her parents, John and Catherine Gurney, believed that girls as well as boys should receive a thorough education including all of the major academic subjects. Catherine herself taught the children these as well as the Bible and she sang the Psalms with them. She spent a lot of time visiting the poor and sick in her neighborhood and Elizabeth would often go with her when she made her rounds. Catherine died after giving birth to her twelfth child and Elizabeth was deeply grieved. She helped raise her younger siblings.

Elizabeth’s upbringing prepared her for what came later in her life. As a young girl, however, she was somewhat rebellious and often made excuses to get out of church services. She was not very serious about religion, but one night on February 4,1798, a Quaker speaker, William Savery, touched her heart. This vain girl who had attended the meeting in purple boots with scarlet laces later said, “I think my feelings that night…were the most exalted I remember…suddenly my mind felt clothed with light, as with a garment and I felt silenced before God; I cried with the heavenly feeling of humility and repentance.” She said that she began to really believe that there was a God. After this, she became less interested in frivolous amusements and tried to live in a more serious manner. She adopted the ways of the plain Friends and even started a Sunday School in her home. She followed in her mother’s footsteps feeding the poor, providing clothes, and reading the Scriptures to them.

About a year later she met Joseph Fry, a banker, and they married in 1799. They would eventually have eleven children. She met the demands of motherhood combined with her work with the poor in her neighborhood, though she often wondered if God had more for her.

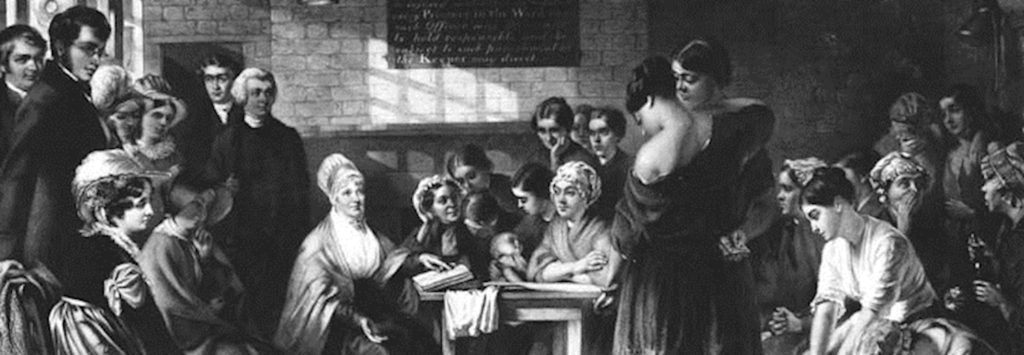

Then in 1813, a visiting Quaker minister from America, Stephen Grellet, came to ask for her help. He had been visiting in the prisons and was horrified at what he saw, especially in Newgate prison. Hundreds of women and their children were crowded into just two cells in the prison. They were sleeping on the floor without nightclothes or bedding in many cases.

When Grellet told Elizabeth about the way the women were treated in Newgate, she decided that she must visit the prison. The next day, she and her sister-in-law went to Newgate prison. The turnkeys (guards) warned them that the women were wild and savage, and they would be in physical danger. However, they went in anyway. On that and further visits, they brought warm clothing and clean straw for the sick to lie on. Elizabeth prayed for the prisoners and began reading the Bible to them.

It is important to remember that the prisons then were very different than the prisons now, especially in the United States. If you have read “David Copperfield” by Charles Dickens, you got a pretty good picture of the conditions for the poor in England in the early nineteenth century. It seems unreal to us now, but debtors could be thrown into prison and were allowed to take their wives and children with them. The entire system in England was corrupt at that time. It was not unheard of for a person to be acquitted, but unable to get out because they could not pay the jailer’s fees, which were often no more than a bribe. There was a death penalty for theft. Prisoners were often transported out of the country to America or Australia. The convict ships were appalling.

At Newgate, where Elizabeth visited, some of the women had been found guilty of various crimes, but others were still waiting to be tried. They did not have warm clothing. The women had to cook, wash and sleep in the same cell. Afterwards Elizabeth wrote that the “swearing, gaming, fighting, singing and dancing were too bad to be described”. Elizabeth began to visit the women prisoners on a regular basis. She actually spent the night several times in some of the prisons and invited the wealthy nobility to come and stay and see for themselves the conditions prisoners lived in.

In 1817, Elizabeth organized a group of women into the Association for the Improvementof the Female Prisoners in Newgate. This group organized a school, and provided materials so the prisoners could sew, knit and make goods for sale. They took turns visiting the prison and reading the Bible to the prisoners. Her kindness helped her gain the friendship of the prisoners and they began to try to improve their conditions for themselves.

On the night before a convict ship was supposed to leave for the Colonies, there would often be a riot. The women resisted being thrown on the ships because it was well known that women would be sick and even die on the voyage. When they got to Australia, they would have nothing and would most often turn to prostitution just to be able to live.

Elizabeth set out to change this situation. For more than 25 years, she visited every convict ship leaving for Australia, and promoted reform of the convict ship system. She saw to it that the women had cloth and sewing materials to make clothing for their own use or to sell when they disembarked so they would not be entirely destitute.

There is much more that could be said about Elizabeth Fry. She was so well known and respected in her own time that her work even received support from Queen Victoria. The Queen took a close interest in her work and the two women met several times. Victoria gave her money to help with her charitable work. In her journal, Victoria wrote that she considered Elizabeth Fry a “very superior person”.

Elizabeth continued her work in prison reform, nurses training, and societies for the poor until her death. She died on October 12,1845 after a short illness.

At this point, we might wonder, “How in today’s society with so much bureaucracy can we help women in prison?” Things have really changed. You can’t just go in to a prison today like Elizabeth could in her day, though you would be a lot safer.

I would like to say that though the obstacles are different, the challenge is the same. Jesus told the disciples in the Gospel of Matthew that those who would follow Him should visit people in prison. We are to care for the poor, the sick, and the prisoners. (see Matthew 25:41-46).

If Elizabeth Fry, devout wife, churchgoer, mother of eleven, and founder of many organizations, could do it in the early 1800’s, with no car, welfare subsidies, protection from guards, or political backing, then we surely ought to be able to accomplish some good.

I also admit that she was not distracted by television, social clubs, modern beliefs on individualism, emphases on our “personal space”, or political correctness. We have our own challenges.

Our advantages include modern technology, protection in the prisons, a lot of free time compared to generations ago, and many organizations that are already helping.

One such is “Prison Fellowship”. There are many good prison outreaches, but PF is a good place to start. They not only have programs for visiting men and women in prison, but many programs for helping on the outside.

Whether you have several hours a month to give or several minutes, there are many ways to help. One that is fun as well as rewarding is the “Angel Tree” program, where gifts are collected for the children of inmates to be given to them at Christmas time. Thank heavens the families of prisoners are no longer thrown in jail with them. Yet they suffer, especially the children.

I urge you to consider the amazing life of Elizabeth Fry. I hope her energy and zeal make you feel guilty enough to at least pray for those in prison. Her life story of compassion has been an inspiration to many.